A Technical Breakdown for Cable Manufacturers Facing Stranding Challenges

Introduction: Why “Define Bunching” Has Become a Critical Production Standard

In today’s wire and cable manufacturing sector, the ability to accurately define bunching has moved from being a theoretical engineering term to an essential operational discipline. As factories push for higher line speeds, tighter diameter tolerances, improved conductor uniformity, and lower production costs, the technical meaning behind “bunching,” “stranding,” and “multi-wire aggregation” has expanded far beyond a simple twist process.

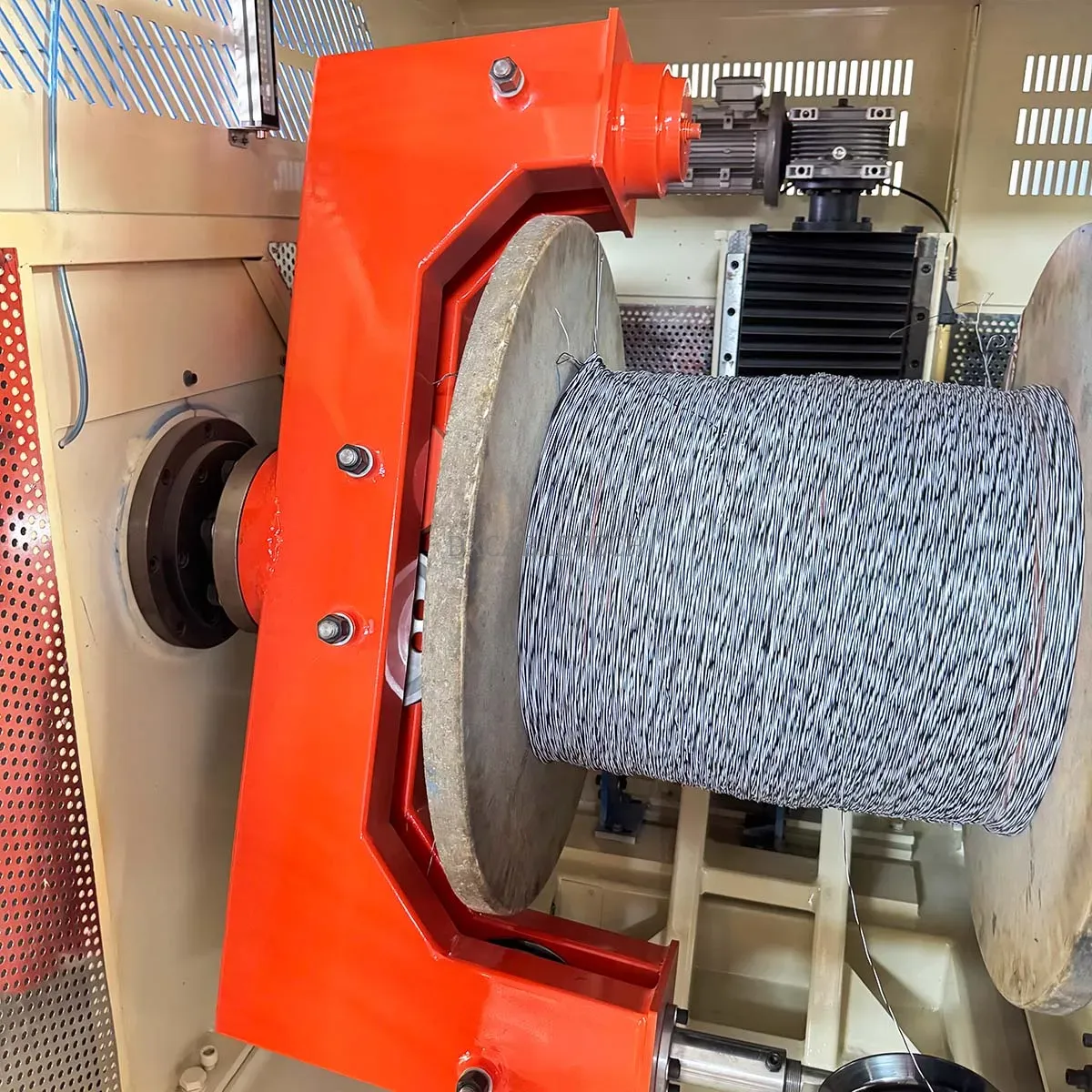

This shift is especially important for companies striving for automation upgrades—such as those using PLC-integrated single twist machines, high-speed bunchers, and precision pay-off systems. Dongguan Dongxin (DOSING) Automation Technology Co., Ltd., founded in 2009 and driven by nearly 30 years of professional R&D leadership from Lin Huazhong, was among the earliest innovators to merge PLC control logic with cantilever stranding machinery. This breakthrough helped solve long-standing speed limitations and improved production efficiency by over 40%.

But even with advanced stranding equipment like single twist machines, double twist bunchers, pair twisters with back-twist systems, and multi-head pay-off racks, many manufacturers still struggle when they attempt to define bunching correctly. Misunderstandings often lead to tension imbalance, conductor deformation, wire breaks, inconsistent lay lengths, or diameter instability during extrusion.

This article will unpack six common problems encountered when plants try to define bunching and apply it on real production floors—helping procurement managers, technical engineers, and production supervisors avoid costly mistakes.

1. Confusing “Bunching” with “Stranding” or “Concentric Stranding”

One of the most widespread issues is the misuse of terminology. When many engineers attempt to define bunching, they mix it up with:

Stranding (wires layered in geometric patterns like 7-wire, 19-wire)

Concentric twisting

Rope lay

Pair twisting

Back twisting

These techniques differ in wire alignment, mechanical behavior, and final cable performance.

Bunching

Multiple wires are twisted together randomly, without a fixed geometric structure. This improves flexibility, conductivity uniformity, and cost efficiency.

Why the confusion matters

When you incorrectly define bunching:

You select the wrong machine (e.g., a double twist instead of a single twist)

You apply incorrect lay ratios

Tension settings become mismatched

Electrical resistance fluctuates

Stranding compactness becomes unstable

A proper definition must emphasize randomized twist accumulation, flexible wire alignment, and no concentric geometry.

2. Overlooking Tension Control as the Foundational Parameter

Another major problem occurs when factories define bunching based only on twist direction or machine type, but ignore pay-off tension.

Tension should be:

Extremely stable

Individually adjustable for each spool

Precisely monitored by sensors when running >2500 rpm

What happens when tension isn’t part of how you define bunching

Wire elongation becomes uneven

Soft annealed copper deforms

The conductor loses roundness

Breakage increases during high-speed output

The extrusion line suffers diameter fluctuation

Most factories blame machines, but the root cause is the absence of tension requirements when they define bunching.

High-end OEMs today include:

Magnetic powder tension systems

Pneumatic dancer arms

Servo-controlled pay-off units

DOSING’s multi-head cable pay-offs and shaftless pay-offs are examples of equipment that help stabilize incoming tension—critical for accurate bunching.

3. Ignoring Lay Length and Lay Ratio When Defining Bunching

Many operators define bunching as simply “twisting wires together,” but this shifts focus away from the most crucial engineering variable:

Lay Length = Cable stability

Lay length determines:

Flexibility

Strain relief behavior

Electrical resistance

Cable roundness

Mechanical strength

Yet in many plants, the lay length is neither measured nor included when they define bunching.

Common mistakes

Using default factory settings from machine vendors

Not aligning lay length with downstream extrusion speed

Zero documentation of optimal lay settings for each product type

Factories must define bunching as a relationship between machine speed, capstan pull rate, and required lay ratio, not just wire twisting.

4. Defining Bunching Without Considering Wire Material and Size

Some plants define bunching only from a mechanical viewpoint, ignoring conductor characteristics:

Copper (soft/annealed/hard)

Aluminum

Tinned copper

Silver-plated copper

Micro-diameter wires (0.05–0.12 mm)

Typical issues caused by ignoring material factors

Small wires (≤0.08 mm) snap easily if bunching speed exceeds mechanical limits

Large wires require different torque balance

Tinned conductors produce inconsistent friction coefficients

Foaming extrusion cables demand stable conductor roundness

When trying to define bunching, wire composition must be explicitly included, or your stranding quality becomes unpredictable.

5. Poor Integration Between Bunching and Downstream Extrusion

Many cable producers fail to connect their bunching standards with the extrusion process. They define bunching solely as an upstream stranding operation—missing how it affects:

Insulation concentricity

Diameter tolerance

Spark test stability

Foaming uniformity

Cooling tank speed compatibility

Why this is a critical mistake

The extrusion line “reads” the conductor.

If the conductor is unstable because bunching was defined without downstream consideration, extrusion shows:

Off-center insulation

Gel formation in foaming lines

Surface dents

Oval conductor symptoms

Inconsistent melt adhesion

A correct engineering definition of bunching must consider the entire cable production chain, not just the twist stage.

6. Using Outdated Machine Assumptions When Defining Bunching

Many factories still rely on older mechanical assumptions when trying to define bunching:

Fixed-speed control

Manual tension wheels

Passive pay-off drums

Zero PLC feedback

No torque compensation

Poor synchronization with capstan pull

This leads to operators defining bunching as if machines from the 1990s are still the standard.

Modern bunching is automation-driven

Today’s high-performance machines integrate:

PLC closed-loop systems

Automatic speed correction

Real-time twist monitoring

Torque-balanced motors

Servo-controlled dancers

Vibration reduction algorithms

DOSING was a pioneer in adding PLC systems to cantilever stranding machines—eliminating speed constraints that limited output for decades.

To define bunching properly, factories must describe:

The role of automation

The required level of machine intelligence

The synchronization between twist and tension

Otherwise, the definition becomes outdated and leads to unstable production.

Conclusion: Why Every Cable Factory Must Redefine How They “Define Bunching”

The term “define bunching” may sound simple, but in modern wire and cable engineering, it is a multi-variable technical standard involving:

Tension control

Lay length

Wire material properties

Automation level

Machine-torque balance

Downstream extrusion compatibility

Ignoring any of these factors leads to the six common problems discussed above—problems that cost factories valuable production time, increase scrap, weaken conductor quality, and reduce competitiveness.

Manufacturers who adopt a modern, engineering-driven definition of bunching will see:

Higher line speeds

Better conductor uniformity

Lower breakage rates

More stable insulation output

Reduced energy waste

Improved cable performance in the field

As the industry continues to automate—especially with innovations like PLC-integrated single twist machines pioneered by companies such as DOSING—having a clear and correct definition of bunching is no longer optional. It is a requirement for any plant seeking long-term growth, stable quality, and global competitiveness.